In a cruel twist of fate, the desultory ruler of all Russia who, by submitting to the imprecations of his military consorts and prematurely mobilizing his army in August 1914, must be deemed most responsible for the ensuing conflagration, three years later became its most prominent victim.

As centuries of repression, a thousand days of horrendous casualties, and a cold, hungry winter -- especially in the remote capital of Petrograd -- coalesced into seething discontent, opportunistic ideologues seized the moment, humbled the Tsar, and brought the three-hundred-year reign of the Romanovs to an abrupt and ignominious end.

The masses must be fed, and thus "it was a shortage of food which provoked what came to be known as the February Revolution." (Keegan, p. 334)

Large-scale street rioting erupted in Petrograd in late February 1917. By March 8, two hundred thousand workers were crowding the center of the city, smashing shops, and fighting the outnumbered and demoralized police. (Keegan, p. 334) Cossack patrols and troops summoned to restore order joined the mob; together they pillaged the capital's huge armory, stormed the local bastilles, freed all political prisoners, and looted shops and homes like ravenous scavengers. (Marshall, p. 271)

En route from army headquarters, Tsar Nicholas II -- "weary, isolated, incapable of action" -- was given the sobering verdict by his senior military commanders, his brother, Grand Duke Nicholas, and the president of the Duma (the Russian legislature), Mikhail Rodzianko: anarchy was imminent, if not a fait accompli, and he must abdicate. The heir apparent Alexis was a hemophiliac, cursed with a constitution too delicate to bear the onerous responsibilities of despotism; the Tsar passed the crown to his younger brother, Michael, who, fearing for his own life amidst the chaos, himself renounced it. (Meyer, pp. 508-512)

Left without a head of state, the apparatus of government devolved upon two rival authorities: the Duma, dominated by thirty-six-year-old Alexander Kerensky, Minister of Justice, and the Soviet of Soldiers and Workers Deputies, an amalgam of army and industry delegates and the self-proclaimed representative body of all political parties, including the Marxist Mensheviks and Bolsheviks.

The Duma established a Provisional Government; but since the Soviet retained veto power, had infiltrated the army, and controlled the railroads and the postal service, it effectively determined military, diplomatic, and economic policy. (Keegan, p. 336)

The two did agree on one course of action: the war with Germany must be continued -- the Provisional Government because it could rally nationalistic fervor to its own cause, and the Soviet because it feared defeat would sabotage the revolution. The only supporters of immediate peace were the Bolsheviks, and their leaders -- Lenin, Trotsky, Bukharin -- languished in exile. (Keegan, p. 336)

But not for long. A Lenin emissary obtained an audience with German commanders Erich Ludendorff and Paul von Hindenberg, and persuaded them that "the way to get Russia out of the war was to send Lenin to spread poison against the Provisional Government." (Marshall, p. 322) Traveling aboard a sealed train -- with guaranteed extraterritorial rights, no inspection of passports, no examination of luggage, no ingress or egress -- Lenin with thirty-two compatriots arrived in Petrograd on April 16 to great fanfare. "He immediately began maneuvering his followers into an antiwar stance calculated to take advantage of public discontent." (Meyer, p. 537)

On the battlefield, despite desperate efforts to preserve morale, Russian fighting capability was rapidly deteriorating. When Kerensky abolished the death penalty for desertion, a million men threw down their weapons -- lured homeward by the promise of land distribution. Behind the line officers and soldiers were shooting each other.

Nevertheless, on July 1, Kerensky ordered his new commander-in-chief, General Aleksei Brusilov -- the hero of the previous year -- to send his motley army once more against the exhausted Austrians. "For two days all went well and several miles of ground were gained. Then the leading units, feeling they had done their bit, refused to persist, while those behind refused to take their place." When the counterattack came, it was more than the Russian soldiers were able or willing to bear. Looting and rape were rampant, as they broke and fled. (Keegan, p. 338)

"On July 8 the Russian Eighth Army essentially went out of existence . . . By July 19 it was the Germans who were advancing, driving a disorderly mob of Russians before them." (Meyer, p. 562) Within two weeks the aggressors had captured Riga, the most important harbor city on the Baltic Coast.

The debacle ruined Brusilov -- who was replaced by General Lavr Kornilov, an outspoken proponent of the war effort. A discredited Kerensky barely survived an abortive rebellion by dissident elements of the Petrograd garrison who, incited by the Bolsheviks, took to the streets to protest a directive sending them to the front.

In September Kornilov attempted to take power himself; his coup failed when his soldiers refused his orders to march on Petrograd. "His fall ended any chance of sustaining the fiction that Russia was still fighting a war. The Provisional Government lost what remained of its authority in the aftermath, since Kerensky's dismissal of Kornilov cost him what support he retained among moderates and senior officers and earned him none from the left." (Keegan, p. 340)

This atmosphere of mounting chaos revived the fortunes of the Bolsheviks. (Stevenson, p. 288) Between July and October their membership rolls swelled from 200,000 to 300,000, and they secured voting majorities in the Petrograd and Moscow Soviets. In September, with the Germans threatening Petrograd from the northern Baltic, they organized their own Red Guard paramilitary force.

Kerensky mistakenly believed he would prevail in a confrontation with the Bolsheviks -- just as he had in July. When he again announced plans to transfer the Petrograd garrison to the front, its regiments responded with this resolution: "We no longer recognize the Provisional Government. The Petrograd Soviet is our Government." (Marshall, p. 326) When he attempted to close two Bolshevik newspapers, on November 6 Lenin's Red Guards -- obeying his exhortation that the hour demanded action -- seized the post offices, telephone exchanges, railway system, bridges, and banks. The next day they easily occupied the Provisional Government's headquarters in the Winter Palace, where no troops were willing to defend the ministers or Kerensky. (Stevenson, p. 312)

On November 8 Lenin announced the formation of a new government, the Council of People's Commissars; its first acts were to proclaim the "socialisation" of land and to issue an appeal for peace, which would commence with a three-month armistice. (Keegan, p. 341)

Ordered to initiate discussions with the enemy for a cessation of hostilities, General N. N. Dukhonin (Kornilov's successor) refused to comply. The newly-appointed People's Commissar for War, Nikolai Krylenko, rounded up a crowd of mutinous sailors; they sped to Dukhonin's headquarters, tore off his epaulets, dragged him from his railway car, and shot him. It was a defining moment of the embryonic revolution, and a harbinger of the endemic brutality that was to follow. (Marshall, p. 327)

Wary of dealing with insurrectionists who were calling for the workers of all lands to rise against the ruling classes (although they indeed had facilitated their triumph), the Germans and Austrians were reluctant to acknowledge Lenin's Peace Decree. When world revolution failed to materialize, the Germans decided to respond, and in doing so bolstered the Bolsheviks' legitimacy.

"On December 3 their delegation, and those of Austria, Turkey, and Bulgaria, met Soviet representatives at Brest-Litovsk, the Polish fortress town on the River Bug, which had been lost by the Russians in 1915. Discussions, frequently adjourned, dragged on into 1918." Over the objections of General Max Hoffmann and Foreign Secretary Baron Richard von Kuhlmann -- who urged conciliation -- Ludendorff prevailed upon the Kaiser to demand the separation of Poland from Russia, the annexation of the Baltic provinces, and even the division of the Romanov expanse into four independent entities -- a truncated Russian proper, Ukraine, Siberia, and a South East area. (Keegan, p. 341)

Both sides lost patience. Leon Trotsky, now negotiating for the Russians, threw up his hands and walked out in disgust. On February 17, 1918, the Germans terminated the armistice and mobilized fifty divisions on the Eastern Front. Unimpeded, the spearheads advanced one hundred fifty miles in five days, capturing three thousand guns, an army of prisoners, and enough rolling stock to double their capacity. (Marshall, p. 333) Lenin, apprehending the loss of Petrograd and the demise of his fledgling empire, relocated the capital to Moscow. Panic-stricken, he resisted Trotsky's entreaties to recommence hostilities and ordered his delegation back to Brest-Litovsk. (Meyer, p. 620)

On March 3 the Russians signed one of the most punitive peace treaties in history. Under its terms, they relinquished territory that encompassed seven hundred thousand square miles, one-third of their population (fifty million people), rail system, and farmland, half of their industry, and over three-fourths of their iron ore and coal reserves. (Meyer, p. 621)

But the victors suffered more than the vanquished. Their administration of this doomed, unmanageable region would require one and a half million troops -- when every available man, gun, and locomotive was needed on the Western Front. The Ukraine breadbasket never produced more than ten per cent of what had been anticipated, while the hungry occupiers consumed thirty rail cars of food daily. Russia's dismemberment at the hands of a victorious and ruthless enemy became a powerful motivation for Britain and France to fight on, regardless of the cost in blood and treasure, in order to avoid a similar humiliation. (Meyer, p. 621)

"As Imperial Russia tottered toward dissolution," and eventual abandonment of its allies, Germany committed two egregious blunders that would provoke and then propel a much more formidable foe into the cauldron. (Marshall, p. 275)

The fateful act had not been inevitable. During 1916 U. S. President Woodrow Wilson had made a determined but fruitless effort to induce the combatants to enter into negotiations on terms he regarded as fair. In 1915 he had convinced Germany to suspend its program of unrestricted submarine warfare by threatening to use American naval power to preserve freedom of the seas. There was little enthusiasm for war among his fellow citizens, particularly those of German descent, who through the German-American Bund campaigned against it. (Keegan, pp. 350-351)

Sinking merchant shipping in international waters by gunfire or torpedo without warning or assisting the crew in evacuation was a breach of maritime law. Endorsed by Ludendorff, its proponent was Admiral Henning von Holtzendorff, chief of the German naval staff; he contended that not only would sinking six hundred thousand tons of Allied, but largely British, shipping a month quickly bring Britain to the brink of starvation, it was also a strategic imperative, lest Germany's capacity to continue the war be exhausted by blockade and attrition. (Keegan, p. 351)

Indeed, from February 1917, when unrestricted attacks by U-boats resumed, sinkings rose from three hundred thousand tons a month to terrifying levels, reaching eight hundred sixty thousand tons in April -- and only began to decline when convoying was implemented the next month. (Marshall, p. 277)

The political repercussions swiftly mushroomed into uncompromising belligerency. On February 3, President Wilson severed diplomatic relations with Germany. On February 26, he requested permission from Congress to arm American merchant ships -- the same day two American women drowned when a submarine sunk the Cunard liner Laconia.

Two days later, with Wilson's blessing, Secretary of State Robert Lansing, released to the press the infamous Zimmerman telegram, which British Naval Intelligence had intercepted on January 17. In unequivocal language, German Foreign Secretary Arthur Zimmerman, a self-styled authority on American politics and culture, proposed, through his ambassador in Mexico City, a German alliance that would enable a victorious Mexico to reclaim its lost territory in Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona. He also suggested that the President of Mexico solicit Japan to switch sides in order to fight against the United States.

The whole idea was preposterous. "Mexico had no cogent military power. Overrun by revolutionaries, she was on the verge of anarchy." (Marshall, p. 276)

When some officials found the telegram too outrageous to be credible and war opponents denounced it as a fraud, Zimmerman compounded his audacity by blithely verifying its authenticity. (Marshall, pp. 276-277)

On March 18, three American ships were torpedoed by U-boats. Two days later Wilson polled his Cabinet; their unanimity was damning. On April 2, the President told Congress that the country "could not choose the path of submission . . . The world must be made safe for democracy." (Marshall, pp. 280-281) On April 6, the United States declared war on Germany by a vote of eighty-two to six in the Senate, three hundred seventy-three to fifty in the House. (Meyer, p. 521)

"Victory is certain . . . We will win it all within twenty-four to forty-eight hours," said the confident, charming new French commander, Robert Nivelle -- the presumptive hero of Verdun -- in describing his plans to British Prime Minister, David Lloyd George. (Marshall, p. 287)

Since the Somme offered no suitable terrain for an abrupt breakthrough, Nivelle would attack on both sides of the river, aiming at the shoulders of the great German salient pointing southwest. While the British struck from the north at Arras against Vimy Ridge, one million two hundred Frenchmen -- three armies, twenty-seven divisions -- would deliver the death blow, or Mass of Maneuver, across the Aisne River against Chemin des Dames. New artillery tactics "would drench the German defenses with fire 'across the whole depth of the enemy position,' destroying trenches, stunning the defenders," and producing the convulsive "rupture." (Keegan, pp. 322-323)

By the time the Germans intercepted a cable disclosing the time and place of the attack, they were already engaged in one of the most daring, improbable tactical moves of the war. Named for a fiendish dwarf-king in Nibelung mythology, Operation Alberich was no less than a massive withdrawal from the Oise salient, a voluntary abandonment of one thousand square miles of conquered territory, and a brilliant contraction of their defensive front, in that it released thirteen divisions and fifty batteries of artillery for use elsewhere. (Meyer, pp. 492-493)

As they retreated, "the Germans systematically vandalized the landscape, pulling down thousands of homes, felling every orchard tree, burning forests, poisoning wells and reservoirs, demolishing bridges and rail lines, and wiping out roadways." (Marshall, p. 289)

The restructured Hindenburg Line elevated defensive warfare to a standard of invulnerability almost inconceivable even in this theater of stalemate. It consisted of, in order, an unoccupied trench line ten feet deep and twelve feet across; five or more rows of barbed or razor wire, concrete blockhouses manned by machine-gun crews, and underground chambers twenty-five feet deep and impregnable to artillery and bombs; and finally two rows of guns each a mile back and sited on reverse slopes wherever possible. (Meyer, p. 495)

This network was complemented by a doctrine which positioned front line defenders beyond the reach of enemy mortars and light artillery, and reserves even further to the rear, where they could counterattack enemy infantry when they had outdistanced their own artillery coverage. (Meyer, p. 494)

In accord with the "Nivelle system," the preliminary bombardment was shorter in duration but double in weight (twenty-eight hundred guns, over two-and-a-half million shells) to that delivered at the Somme the previous July.

Early on the morning of April 9, the infantry of the Canadian Corps, four divisions strong, "moved undetected to within a hundred and fifty yards of the German defenses through a maze of sewers and tunnels that honeycombed the earth beneath Arras." (Meyer, pp. 530-531) Upon emerging, they advanced swiftly under the protection of a perfectly-timed creeping barrage to a depth of up to three miles, claimed nine thousand prisoners, and stormed the slopes of Vimy Ridge; from the summit, the whole Douai plain, crammed with German artillery and reserves, lay open before them. Then, with victory within their grasp, they became bogged down in knee-deep mud and, inevitably, were halted by a predicated pause. (Keegan, pp. 325-326)

The next day the first German reserves appeared to plug the gap. An Australian division ran up against uncut wire which the handful of accompanying tanks could not penetrate. "An intermission was ordered, to allow casualties to be replaced and the troops to recover . . . When the battle was resumed on April 23, the Germans had reorganized and reinforced and were ready to counterattack in every sector." (Keegan, p. 326)

Field Marshal Douglas Haig labored on for several more weeks, partly to support Nivelle, partly encouraged by his initial success. "By the time it all ended, the Germans had taken one hundred eighty thousand casualties, Haig's armies a hundred fifty-eight thousand. Back in London, Lloyd George could not contain his disgust at the expenditure of so many men for such limited results." (Meyer, p. 532)

Scoffing at the pessimistic prognostications of his army group commander, General Alfred Micheler, and Minister of War Paul Painleve, the bombastic Nivelle launched his own attack against the southern shoulder of the salient at 6:00 o'clock on the morning of April 16. "From start to finish it was a contest between an offensive of the most conventional kind -- more than a week of intense artillery preparation, massed formations of infantry slogging in plain view -- and the Germans' new defense in depth: wide, deep trenches, acres of treacherous wire, well-protected machine guns, and reserves positioned far beyond the reach of Nivelle's batteries." (Meyer, pp. 534-535)

Even if the assault forces should reach their objective, they would be too weary and battered to resist the fresh troops looming before them. (Keegan, p. 327)

An encouraging jump-off soon disintegrated into a massacre too reminiscent of the Somme. Cold rain turned to sleet, and then snow -- obscuring the field and slowing the pace of the advance. "Machine guns -- scattered in shell holes, concentrated in nests, suddenly appearing at the mouths of deep dugouts or caves -- took a murderous toll on troops struggling up the rugged slopes." The creeping barrage, by which the infantry should have been protected, soon left them behind -- and dangerously exposed. "Men pulling themselves up by clinging to the stumps of trees were impeded by wire obstacles of every conceivable variation." (Keegan, p. 328)

Tanks might have broken the wire, but, of the one hundred twenty-eight Renault two-man models thrown into the fight -- the first to be so deployed by the French -- thirty-two were blown to bits, twenty-eight failed mechanically, and the rest bogged down in the mud. (Keegan, p. 329)

Well-rested German reserves sent the French vanguards reeling back to their starting point.

Nivelle had predicted a penetration of eight thousand yards the first day; but when darkness fell, his line had advanced only six hundred. On the third day the Chemin des Dame road, crossing the ridge, was reached, but the decisive high ground remained unobtainable.

Nivelle had promised to shut down his offensive if a breakthrough was not achieved in forty-eight hours, but like so many deluded generals who had traversed the same ground before him he stubbornly persisted -- for ten days, at a cost of two hundred thousand men. Finally, French President Poincare ordered an end to the bloodbath, sacked Nivelle, and replaced him with Henri Petain. (Keegan, p. 329)

Dispirited, disgusted, demoralized, French soldiers "rioted, threw down their rifles, and set up committees to replace their officers. In some cases they deserted their stations en masse and ran off rearward, stood their ground sullenly, or fell in so drunk they could not march." (Marshall, p. 292)

Whatever the movement was called -- mutiny, strike, or, in the government's euphemistic phraseology, "collective indiscipline" -- it was a spontaneous declaration by the troops that they could no longer subsist in intolerable conditions nor continue to be sacrificed to no purpose. (Meyer, p. 541)

Petain acted quickly and firmly, while maintaining an admirable balance between severe punishment and compassionate leniency. Ringleaders were identified, arrested, and brought to trial. Approximately five hundred were sentenced to death, although only forty-nine were executed. Hundreds of others were imprisoned or exiled to French colonies. (Meyer, p. 541)

On the other side of the ledger, Petain did not ignore the abuses that had sparked the rebellion. His men were demanding better food, decent shelter for those not on the front line, fairness in the granting of leave, and an end to the pointless offensives that had squandered so many lives. He promised to address those demands, and he saw to it that his promises were kept. (Meyer, p. 541)

Whether because of his initiatives, or simply because it was so thoroughly shaken, the French Army did not attack nor actively defend any of the sectors on the Western Front -- of which it held two-thirds -- between June 1917 and July 1918.

Two and one-half million soldiers had been killed on that Front; total casualties had reached an astronomical seven million. The one man not discouraged by the carnage was British Field Marshall Sir Douglas Haig. (Marshall, p. 299)

Fueled by reports from his consistently optimistic intelligence chief, General John Charteris -- Germany was riddled with strikes and unrest, troop morale was falling, the army was on its last legs -- the indomitable Haig believed a major victory was within his grasp. (Hochschild, p. 277) He and his staff devised a plan that would combine a new offensive out of the Ypres salient with an amphibious landing along the Belgian coast. Compelled to surrender its U-boat ports, Germany would be exposed on two fronts.

Haig needed an anchor for his Ypres attack and a hammer to convince doubters that his strategy was feasible; Second Army commander Sir Herbert Plumer gave him the Messines Ridge, from which German artillery spotters had long dominated the area.

By May Plumer's tunneling companies had driven forward under the ridge nineteen galleries -- some half a mile long and a hundred feet deep -- and packed the end chambers with a million tons of explosives. On the morning of June 7, after a week of bombardment by the heaviest concentration of artillery on any front up to that time, the mines were detonated. (Meyer, pp. 556-557) "Lloyd George, working in his study at 10 Downing Street, heard the rumble and felt the quake." (Marshall, p. 300-301)

Plumer's nine infantry divisions stormed the ridge, which had been transfigured into giant craters seventy feet deep, overwhelmed the shell-shocked survivors -- more than twenty thousand men had been killed or maimed -- and took possession of the remnants of the German trenches with negligible casualties. (Meyer, p. 558)

The success at Messines Ridge did nothing to ease Prime Minister Lloyd George's conscience. "He summoned Haig to a June 19 meeting with his recently created Cabinet Committee on War Policy." (Meyer, p. 558)

He was relentless in his interrogation and criticism. "He wanted to know why the generals believed a Flanders offensive could succeed this time, what their estimate of casualties was, how the enemy's forces were disposed, and what the consequences of failure might be." (Meyer, p. 559) He lobbied for delay -- since the Americans were coming -- and proposed a series of small attacks rather than a possible repetition of the Somme. In the end, he yielded without being convinced; unable "to impose his strategical views on his military advisers, he was obliged to accept theirs." (Keegan, p. 358)

The requisite bombardment began on July 15. For two weeks, along fifteen miles of front, three thousand guns -- more than double the density at the Somme -- fired off four million shells weighing sixty-five thousand tons -- four times the quantity at the Somme; the German Fourth Army incurred thirty thousand casualties before the British moved single step. (Meyer, p. 571)

The Flanders position was one of the most formidable on the Western Front. "From the low heights of Passchendaele, Broodseinde, and Gheluvelt, the enemy front line looked down on an almost level plain from which three years of constant shelling had removed almost every trace of vegetation." Nine layers of defense awaited the oncoming hordes: a line of listening posts, three of breastworks sheltering the first resisters, a battle zone of machine gun posts and pillboxes, and finally counterattack units ensconced in concrete bunkers alongside artillery batteries. (Keegan, p. 358)

To this impenetrable barrier nature had added another ghastly complication: the water table on the plain was less than two feet below ground. The heavy rains of late summer would frequently flood the area, churning it into a bottomless, gluey, muddy mess. To make matters worse, Haig's bombardment destroyed the few remaining canals and drainage ditches, and hollowed out thousands of craters that quickly filled with water. (Meyer, p. 555)

As a result, one gruesome fact was to separate Passchendaele from the great paroxysms of bloodshed that preceded it: "in addition to falling victim to German fire, thousands of British soldiers, nowhere near the sea, drowned." (Hochschild, p. 285)

"The offensive went off at 3:50 A.M. on July 31, with seventeen Entente divisions advancing and seventeen waiting in the rear" -- a total of nearly half a million men. "Ten divisions of Hubert Gough's Fifth Army were the battering ram, their assignment to force the Germans back and set the stage for reserves to come forward." (Meyer, p. 575)

Those units managed to fight their way through the first German zone and into the second, penetrating as far as two miles at some points. Then, at two in the afternoon, the Germans opened fire with field guns positioned on elevated ground to the north and south of the newly-created salient. "To the rain of shells was added a ferocious downpour which soon turned the broken battlefield to soupy mud." (Keegan, p. 361) The British suffered heavy losses and were forced to pull back. (Meyer, p. 575)

"Rain was falling in torrents when Haig resumed his attack on August 2. With the Flanders drainage system in ruins, every hole filled with water and the ground became a morass to a depth no man's foot could reach." (Meyer, p. 576)

"Guns could barely be moved, and mules and horses pulling ammunition wagons sank up to their stomachs and had to be dug out. Ambulances carrying wounded soldiers skidded off slippery roads . . . Cold-weather greatcoats that were not waterproof absorbed mud and water like a sponge, adding up to thirty-four pounds to their weight." Wounded men who crawled into shell holes for safety were buried under water. (Hochschild, pp. 285-286)

To the fear of drowning was added new horror: mustard gas. "No mask was proof against it. It burned through clothing,worked its way into flesh, destroyed vision and choked out life." (Marshall, p. 322) "The worst off were soldiers who had breathed droplets in the air, for their blisters were internal, gradually swelling to seal throats and bronchial tubes fatally shut, a process that might take as long as four or five weeks." (Hochschild, p. 287)

On August 4, with the number of French and British casualties up to sixty-eight thousand, Haig finally ordered a halt until the rain stopped and the ground could dry out. (Meyer, p. 576)

Haig was determined to continue no matter how high his losses mounted or how soaked the battlefield became. A series of assaults on the Gheluvelt Plateau which gained little ended the first phase of the Third Battle of Ypres. In three and a half weeks troops had advanced two miles -- under "constant exposure to enemy view in a landscape swept bare of buildings and vegetation, sodden with rain and in wide areas actually under water, onto which well-aimed shellfire fell almost without pause." (Keegan, p. 365)

The weight of the campaign now shifted to the wily veteran, Sir Hubert Plumer, and his Second Army. Plumer adopted a "bite and hold" approach, in which, after a long, intense bombardment, soldiers would advance in fifteen hundred yard stages -- not far enough to trigger a counterattack -- capture the thinly-manned forward ground, and hastily entrench themselves. These tactics produced remarkable successes at Menin Road on September 20, at Polygon Road on September 26, and at Broodseinde on October 4. (Keegan,p. 365)

The last was a day of disaster for the Germans. Desperate to counter Plumer's scheme, they positioned substantial numbers in a strong forward line to block any easy initial gains. Having a mere handful of days to construct adequate defenses, they were slaughtered wholesale by Plumer's barrage, as were their reserves, also located well within artillery range. (Meyer, p. 580)

Deliverance came from the heavens -- a downpour that turned Flanders into "an enormous shallow lake; every shell hole and piece of low ground filled to the brim." Plumer and Gough advised shutting down the campaign, but Haig would not hear of it. Since Plumer was now deployed along a line that would be difficult to hold during the coming winter, and a withdrawal to higher ground was for Haig unthinkable, the only acceptable course, he declared, was to push forward to Passchendaele Ridge. (Meyer, pp. 581-582)

"Virtually every British division in the Ypres salient having been reduced to tatters, the lead role would be assumed by divisions from the Commonwealth" -- ANZACS (Australians and New Zealanders) and Canadians." (Meyer, p. 582)

In what was called the First Battle of Passchendaele, the ANZACS tried on October 12 to reach the trenches and pillboxes on the highest point of ground east of Ypres, one hundred fifty feet above sea level, the last obstacle between the British and the German rear. The conditions were impossible. Standing water or mud covered everything. Guns, an entire railway, pack mules all sunk out of sight; shells disappeared without exploding because the surface had become too soft to activate their fuses. "Caught in front and flank by machine-gun fire, the ANZACS eventually retreated to the positions from which they had set out on that sodden day." (Keegan, p. 367)

Ordered to attack the ridge on October 26, Canadian Corps commander Sir Arthur Currie predicted it would cost him sixteen thousand men; he overestimated by three hundred. In four separate assaults, the last on November 6, under pounding rain, his troops finally drove the Germans off a large enough portion of Passchendaele Ridge for Haig to claim a Pyrrhic victory. Nearly seventy thousand of his soldiers had been killed in the muddy wastes of the Ypres battlefield and over one hundred seventy thousand wounded -- to conquer four and a half miles. (Keegan, pp. 367-368)

The patently meaningless sacrifice of the Canadians prompted their Prime Minister, Sir Robert Borden, to seize Lloyd George by the lapels and shake him. (Hochschild, p. 287) But it was left to Lloyd George to pronounce the fitting epitaph on this hellish swampland: "Blood and mud, blood and mud, they can think of nothing better." (Meyer, p. 571)

Haig was not done. On November 20, near Cambrai, east of the old Arras battlefield, he sent nineteen divisions and the largest force of tanks yet assembled against a thinly defended section of the Hindenburg Line. "Within four hours the attackers had advanced in many places to a depth of four miles at almost no cost in casualties."

But the commander of the division assigned to the center of the formation, General G. M. Harper, did not like tanks; he believed they attracted enemy artillery fire, and thus he kept his infantry too far to the rear to cover those in his sector. Many were destroyed by trained sharpshooters. While on the left and right the whole German position had been penetrated, a clear-cut breakthrough was stymied. (Keegan, pp. 370-371) "On November 30 a counterattack by twenty German divisions recovered almost all the lost ground." (Meyer, p. 587)

With the Russians in revolution, the French in disarray, the British mired in Flanders, a fourth Allied army would effectively capitulate before the nightmarish clock ran out on 1917. Italy had been lured into the Entente by the promise of territorial spoils in Trentino, Istria, and Dalmatia; even before disaster struck, it had paid mightily for its greed. Its army was ill-equipped, untrained, and ineptly led; its Chief of Staff, the imperious, tyrannical General Luigi Cadorna, seriously advocated the shooting of every tenth man in units that failed to perform to his satisfaction.

The object of Cadorna's series of campaigns, the bridgehead of the Isonzo River at the fortress city of Gorizia, was guarded in the north by the Bainsizza plateau and on the south by the Carso plateau -- "a howling wilderness of stones sharp as knives." Thus, while the Italians usually outnumbered their Austrian foes, often by as much as two to one, their statistical superiority was negated by a mountainous terrain which constricted operations and allowed the Austrians to dominate the elevated positions. It was a topographical problem that defied solution; for the Italian Army every maneuver became a backbreaking struggle upgrade. (Marshall, p. 173-174)

There had been four Italian offensives in 1915 -- the First, Second, Third, and Fourth Battles of the Isonzo -- "all staged in the same area, all monotonously ineffective, all mournfully wasteful." For a few worthless acres of soil, in repeated forlorn attempts to scale the towering crags and gain the Ljubljana Pass, the Italians had spent the blood of a quarter million soldiers. (Marshall, pp. 174-175)

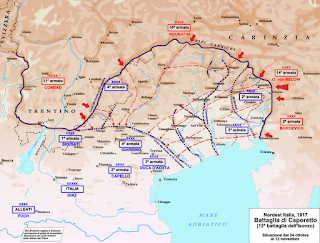

Two more Battles of the Isonzo (the Tenth and Eleventh, all told) in May and August 1917 had cost Cadorna another two hundred eighty thousand casualties. Austria's losses had been commensurate. Warned by his generals that his army was unlikely to survive another Isonzo, Emperor Karl appealed directly to Kaiser Wilhelm for reinforcements. Ludendorff appropriated infantry, artillery, and aircraft from units stationed in the Baltic, Romania, and Alsace-Lorraine, and reluctantly created a new German Fourteenth Army. He sent it southward under the veteran Otto von Below with orders to stabilize the Italian front. (Meyer, pp. 583-584)

Cadorna had left himself dangerously exposed to entrapment. "By pushing across the Isonzo, but not far enough, he had left two bridgeheads in the enemy's hands, which offered them the opportunity to drive down the valley from north and south and link up behind the whole Italian Army." He had kept "his front line full of troops, where they were most likely to be cut off, and positioned his reserves too near the rear, whence they would have difficulty arriving at the front in the event of a crisis." (Keegan, p. 347)

Italian gas masks were known to be ineffective. A preliminary bombardment of mustard gas followed by explosives wreaked havoc in the Italian trenches. Then, on the morning of October 24, two point divisions attacked north and south along the Isonzo toward Caporetto. Employing innovative infiltration tactics, the Germans and the Austrians pierced the steep defile of the river valley, bypassed enemy strongholds, and carved out an enormous fifteen-mile gap in the Italian front. (Keegan, p. 348)

Among those in the vanguard was company commander Erwin Rommel. Thrusting beyond his flanking contacts, he broke through a key height in the Italian rear, and eventually captured an entire regiment singlehandedly. (Keegan, pp. 348-349)

Four Italian divisions were isolated and surrounded. Larger concentrations of troops north and south were threatened by the deep German penetration. By the third day of the battle the whole front had collapsed. Hundreds of thousands of soldiers streamed down from the mountain in headlong retreat. The Austrians were astonished to encounter organized units marching toward them into captivity. (Keegan, p. 349)

"Below's instructions were to proceed no farther than the Tagliamento River, which flows southward into the Adriatic west of the Isonzo, but his forces attained that objective so quickly that they pushed on in hot pursuit." The Italians continued to flee until they reached the Piave River twenty miles beyond the Tagliamento. There, on November 3, Below, having outrun his lines of supply and facing the onset of winter, ordered a halt. (Meyer, p. 584)

He had advanced eighty miles in eleven days, collected two hundred sixty-five thousand prisoners, conducted one of the war's most spectacular campaigns, toppled a government, and inflicted irreparable harm to the reputation of the Italian Army, from which it was never able to recover. It was the crowning blow to Italy's Great War misadventure, whose final toll was six hundred thousand lives. (Meyer, p. 585)

Though battered and exhausted, the Entente Powers could look westward to their potent new ally for renewed energy and fresh manpower. The looming question for the new year was whether Germany could muster enough of their own in time to render the advent of America too little and too late.

REFERENCES

Hochschild, Adam. To End All Wars: A Story of Loyalty and Rebellion 1914-1918. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2011.

Marshall, S. L. A. World War I. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1964.

Meyer, G. J. A World Undone: The Story of the Great War. New York: Delacorte Press, 2006.

Keegan, John. The First World War. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1999.

Stevenson, David. Cataclysm: The First World War as Political Tragedy. New York: Basic Books, 2004.

Saturday, June 23, 2012

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)